Introduction: Understanding Centrifugal Turbomachinery

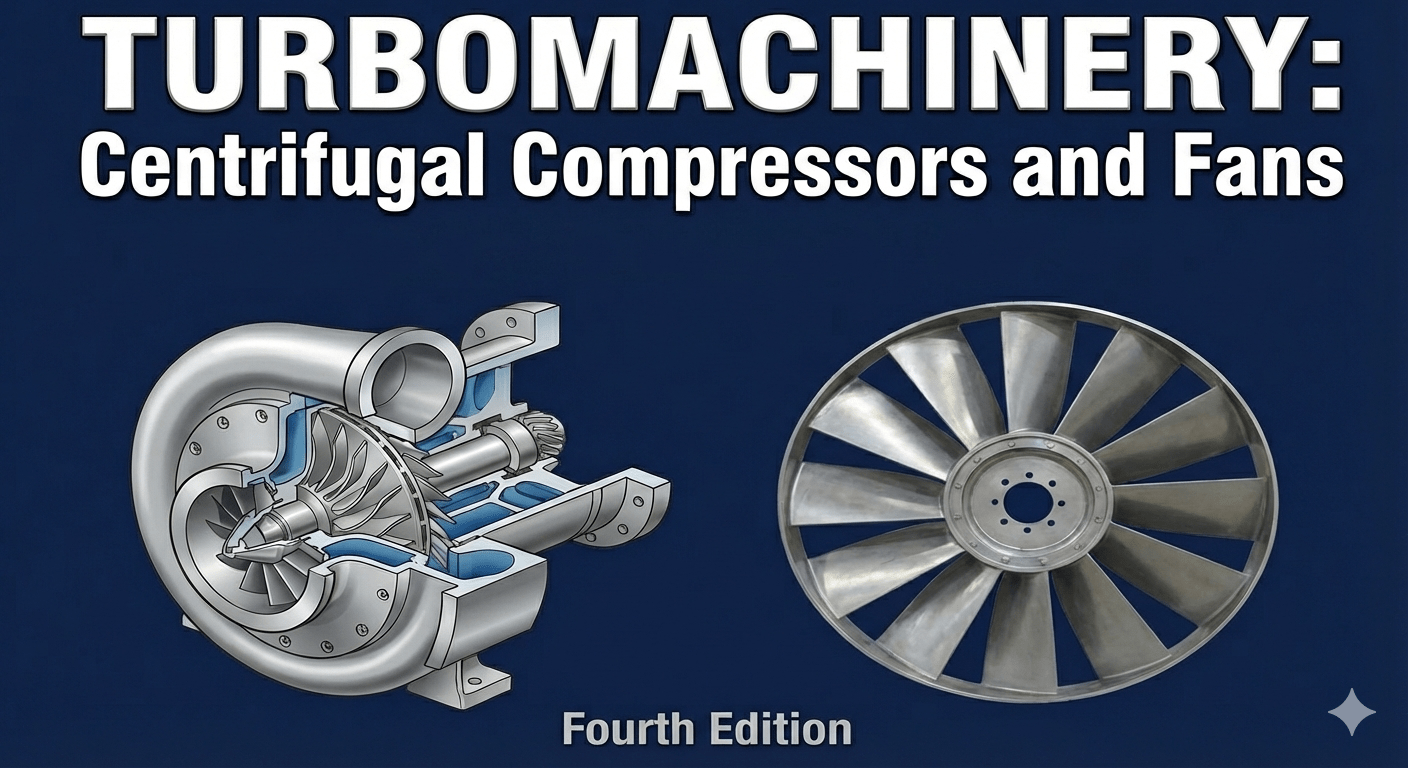

Centrifugal compressors and fans compress air, gases, and vapors using rotating impellers that accelerate fluid outward, creating pressure rise through centrifugal force. Unlike reciprocating compressors (piston-based), centrifugal machines deliver smooth, continuous flow with fewer vibrations and higher efficiency at moderate-to-high flow rates.

Global operating scale: ExxonMobil operates 2,000+ centrifugal compressors in refineries and pipelines. Shell uses high-speed compressors reaching 30,000 RPM for natural gas processing. HVAC systems worldwide use 10+ million centrifugal fans in cooling towers and building ventilation. One failure costs $50K-$5M depending on application.

This guide explains aerodynamic principles, design fundamentals, performance characteristics, and failure prevention using S.L. Dixon’s turbomachinery physics combined with real industrial case studies from USA refineries, UK manufacturing plants, and European power stations.

Table of Contents

Centrifugal Compressor Aerodynamics: The Physics Foundation

Centrifugal compression converts rotational kinetic energy into fluid pressure through two stages:

Stage 1: Acceleration in Impeller

Fluid enters the impeller eye (center) at low velocity (10-20 m/s). Curved blade passages accelerate it radially outward. Exit velocity reaches 100-200 m/s depending on blade design and rotational speed. Centrifugal force pushes fluid outward: Force = m × ω²r (mass × angular velocity² × radius).

Stage 2: Deceleration in Diffuser & Volute

High-velocity fluid exits impeller into diverging diffuser vanes (stationary curved passages). Velocity slows progressively while pressure rises. Bernoulli’s principle explains the conversion: ½ρV² (kinetic energy) → Δp (pressure energy). Well-designed diffusers recover 50-70% of kinetic energy as pressure rise. Poor diffusers waste 30-50% as turbulent heat.

Pressure Coefficient: Engineers use dimensionless pressure coefficient (Cp) to compare different designs:

textCp = (p₂ - p₁) / (½ρV₁²)

Higher Cp = more efficient pressure recovery. Typical ranges: Cp = 0.5-0.9 for industrial compressors.

Mach Number Effects: At high speeds (>0.8 Mach), compressibility becomes significant. Air density changes 10-20% through the impeller. Supersonic flow (>1.0 Mach) creates shock waves that reduce efficiency 5-15%. Design must consider transonic/supersonic regions at impeller inlet and exit.

Real thermodynamic cycle: Isentropic efficiency measures ideal vs. actual compression:

textηis = (ideal work) / (actual work)

ηis = ln(P₂/P₁) / ln(ρ₂/ρ₁) × (theoretical path) / (actual path)

Typical industrial compressors: ηis = 75-88% (high-end designs reach 92%). 1% efficiency loss = $50K annual electricity cost for continuous 1,000 kW compressor.

Impeller Design: The Heart of Compressor Performance

Impeller types determine pressure ratio, flow capacity, and efficiency:

Radial Impellers (most common): Blades exit perpendicular (90°) to shaft. Creates highest pressure rise but moderate flow capacity. Pressure ratio: 1.5-3.0 per stage (can compress 1 atm to 1.5-3 atm in single stage). Used in: natural gas processing (10 bar+), high-pressure gas applications, process compression.

Backward-Curved Blades: Exit angle 20-30° backward from radius. Reduces radial thrust forces on bearings. Higher efficiency (80-88%) due to reduced secondary flows. Pressure ratio: 1.3-2.5 per stage. Most practical industrial choice balancing efficiency and reliability.

Forward-Curved Blades: Curves follow rotation direction. Lower efficiency (60-75%) but higher pressure capacity. Used in: low-speed fans (<3,000 RPM), HVAC applications where efficiency less critical.

Blade Geometry Details:

- Blade thickness: Thicker blades resist stress but add weight (imbalance risk)

- Number of blades: 4-9 typical; more blades = smoother flow but higher cost

- Blade curvature: Smooth aerodynamic curves prevent flow separation (turbulence)

- Suction surface roughness: Surface finish <0.8 μm reduces boundary layer losses

- Blade chord length: Longer chords = higher pressure but higher stress

- Meridional flow path: Controls acceleration through impeller—critical for efficiency

Impeller Materials:

- Cast aluminum: Standard (low cost), -50°C to +150°C, limited pressure

- Ductile iron: Higher strength, pressure to 30 bar, density 3x aluminum (imbalance risk)

- Forged steel: Highest strength, pressure to 100+ bar, thermal stress resistance, cost $50K-200K

- Titanium: Aerospace applications, weight 40% less aluminum, cost premium 10-20x

Impeller Balancing: Rotating impeller creates centrifugal force. Unbalance causes 1x RPM vibration. Balance tolerance: ISO 1940 Grade 1.0 (precision) for high-speed compressors. Imbalance >0.001 in/s causes bearing life reduction 50-80%.

Real design example: Natural gas compressor at 15,000 RPM requires:

- Exit velocity: 180 m/s (heat generation managed by intercooling)

- Pressure ratio: 2.5 (requires 3 stages)

- Mach number: 0.92 (transonic flow—design complexity increases)

- Impeller diameter: 300 mm (controlled by stress limits in forged steel)

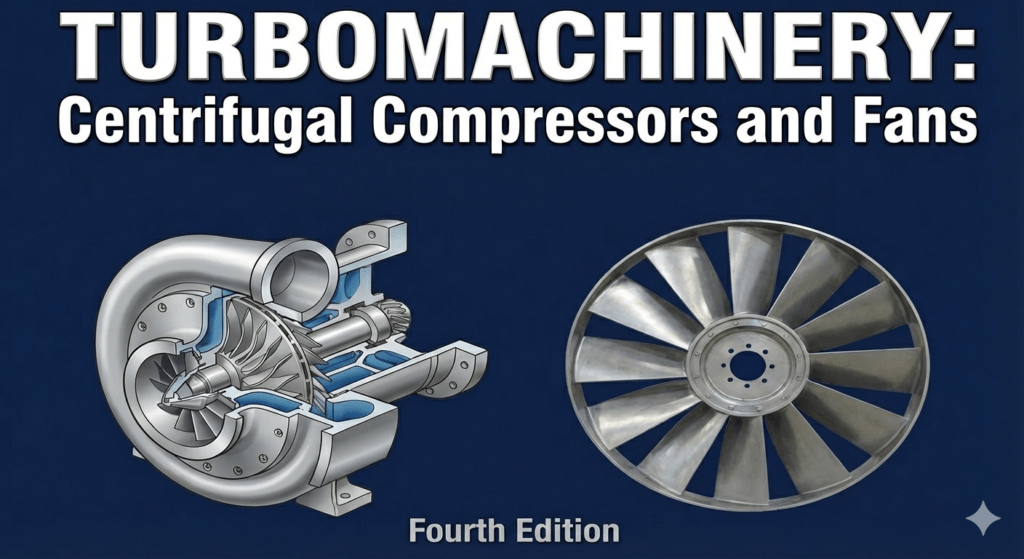

Centrifugal Fan Design: Lower Pressure, Higher Flow Applications

Fans compress air at low pressure (0.05-0.5 bar) for cooling towers, HVAC, dust collection, pneumatic transport. Different design from compressors despite similar centrifugal principle.

Key differences from compressors:

- Lower pressure ratio: Fans deliver 1.05-1.2 atm (5-20% pressure increase)

- Higher flow capacity: 1,000-100,000 m³/h vs. compressors (10-5,000 m³/h)

- Lower speed: 600-3,600 RPM vs. compressors (5,000-50,000 RPM)

- Simpler design: Fewer blade passages, less critical tolerances

- Larger physical size: Lower speed requires larger diameter impeller

Fan Types:

Centrifugal Fans (backward-curved): Most efficient (75-85% for industrial designs). Used in: cooling towers, ventilation, air-conditioning. Pressure rise independent of speed—stable operation across flow range.

Radial Fan (forward-curved): Lower efficiency (60-70%) but simpler, cheaper. Pressure rise increases nonlinearly with flow—prone to surge at low flow. Used in: small HVAC systems, dust collection.

Axial Fans: Propeller-type, high flow-low pressure. Different fluid mechanics than centrifugal. Not covered in this centrifugal focus.

Real cooling tower fan: Cools 50,000 m³/h water at 10°C temperature drop. Fan pushes 100,000 m³/h air through tower. Design:

- Backward-curved impeller: 2 meters diameter, 1,200 RPM

- Pressure rise: 0.15 bar (overcome tower resistance)

- Motor power: 150 kW

- Efficiency: 82% (operating cost $50K/year)

Performance Maps and Operating Envelopes

Compressor performance defined by pressure-ratio vs. flow-rate map showing:

Performance Curve (characteristic line): Solid line showing actual compressor performance. Plots discharge pressure vs. inlet flow rate. Different curves for different rotational speeds (iso-speed lines).

Surge Line: Left boundary of map—minimum stable flow rate. Beyond surge line = unstable oscillations where pressure spikes, then collapses, then repeats (cycle period 0.1-1 second). Causes: flow reversal, blade stall, impeller vibration.

Choke Line: Right boundary of map—maximum flow rate at given speed. Exceeding choke creates sonic conditions (Mach 1.0) in throat section. Cannot increase flow further even with lower discharge pressure.

Best Efficiency Point (BEP): Peak efficiency typically at 70-80% of maximum flow. Operating far from BEP wastes electricity and creates heat ($$$ and reliability penalty).

Operating Envelope: Safe operating region between surge and choke lines, typically 50-100% of design flow. System must operate within this region.

Real example: 100 m³/h compressor at 3,600 RPM

- Surge point: 50 m³/h (cannot go lower without surge)

- BEP: 85 m³/h (peak 88% efficiency)

- Choke point: 120 m³/h (cannot go higher)

- Safe operating range: 50-120 m³/h

- Optimal operating point: 85 m³/h (save $30K/year electricity vs. 50 m³/h operation)

Surge Prevention and Control Systems

Compressor surge is catastrophic—pressure oscillations (0.1-1 second period) destroy bearings, seals, and couplings within hours. $500K-$5M damage if not detected and corrected.

Root causes of surge:

- Flow reduction below surge limit (valve closure, downstream restriction)

- Ambient temperature drop (reduces inlet flow)

- Inlet air filter clogging (reduces inlet pressure, raises pressure ratio)

- Discharge line blockage (forces operation left of surge line)

Surge prevention systems:

1. Anti-Surge Valve (ASV) (most common): Proportional valve that recirculates excess flow back to inlet when pressure approaches surge. Reduces discharge pressure, moves operation away from surge. Response time: 100-500 milliseconds. Cost: $20K-50K installed.

2. Inlet Guide Vanes (IGV): Adjustable vanes at impeller inlet reduce incidence angle, lowering pressure rise. Prevents surge by reducing flow tendency. Less effective than ASV but lower cost ($10K-20K).

3. Variable Frequency Drive (VFD): Reduces motor speed when flow approaches surge limit. Proportional to flow³ relationship—10% speed reduction = 27% power reduction. Prevents surge while saving electricity. Cost: $50K-100K but ROI in 1-2 years.

4. Inlet Throttling: Simple valve reducing inlet flow when needed. Wasteful (throttles pressure drop, wasting energy) but cheapest option ($5K-10K).

Best practice: Multi-layer defense combines ASV + VFD + pressure monitoring. Prevents both surge (pressure spikes) and stonewall (flow blockage).

Real case: Shell Canada Natural Gas Compressor:

- Inlet conditions vary (temperature -20°C to +30°C, pressure 10-50 bar)

- Without anti-surge system: surge every 2-3 days = damage, shutdowns

- With integrated ASV + VFD: zero surge incidents over 5-year period

- Annual maintenance cost: $50K (valve overhauls, VFD maintenance)

- Production protection: $100M+ value

Centrifugal Compressor Bearings and Rotor Dynamics

High-speed rotors (15,000-50,000 RPM) create unique bearing challenges:

Critical Speed: Rotor natural frequency where shaft deflection resonates with rotating speed. At critical speed, small imbalance creates large vibration. For flexible rotor design, operation above critical speed (15-30% higher) reduces bearing loads compared to operation at critical speed.

Real rotor: Compressor at 20,000 RPM

- Critical speed: ~15,000 RPM

- Typical operation: 20,000 RPM (above critical)

- Vibration at critical speed (if briefly encountered): 5-10 mm/s RMS

- Vibration at operating speed: 2-3 mm/s RMS (safe)

Bearing Types for High-Speed Compressors:

Tilting-Pad Journal Bearings: Preferred for speeds >10,000 RPM. Pads tilt as rotor spins, optimizing oil film thickness. Self-aligning—tolerates misalignment. Excellent damping—prevents resonance. Cost: $50K-150K per bearing.

Rolling Element Bearings (ball/roller): Limited to ~10,000 RPM. Higher speeds cause centrifugal force to increase bearing preload, causing skidding and failure.

Magnetic Bearings (active): Suspended rotor using magnetic fields without contact—zero friction, zero wear. Eliminates traditional bearings entirely. Requires continuous power and control system. Cost: $500K-$2M but unlimited lifespan. Used in: critical offshore platforms, high-reliability aerospace applications.

Lube Oil System: Continuous supply of clean oil essential. Typical flow rate: 10-50 liters/minute per bearing. Temperature control: 40-60°C optimal (cooler = higher viscosity = higher friction; hotter = oil oxidation). Separator removes entrained gas—compressed air mixed with oil causes bearing cavitation (foam). Coalescer removes water—water <200 ppm required (water above this rusts bearing races).

Real Industrial Case Studies: Global Centrifugal Compressor Applications

Case Study 1: ExxonMobil Baytown Refinery (Texas, USA)

Application: Natural gas compression, 5-stage centrifugal compressor, inlet 10 bar, discharge 100 bar, 500 m³/h flow

Challenge: Surge oscillations occurring 2-3 times daily during load changes. Pressure spikes 110 bar (exceeding 100 bar design limit), causing bearing misalignment vibration and coupling stress failures.

Root cause analysis: Anti-surge valve installed but response time too slow (1,000 ms). By time valve opens, surge already triggered.

Solution: Replaced ASV with proportional valve (200 ms response), added pressure relief valve (quick response, 50 ms), and VFD for speed trim (responds in 1,000 ms but eliminates root cause).

Result: Zero surge incidents over 18-month period. Annual maintenance cost: $50K (valve overhauls). Production protection: $500M+ (prevents 48-hour shutdowns).

Lesson: Surge prevention critical in multi-stage compressors—pressure accumulates through stages, creating massive spike potential.

Case Study 2: Siemens Manufacturing Facility (Munich, Germany)

Application: Process air compression for pneumatic systems, centrifugal fan-type compressor, 1,800 RPM, 200 m³/h, 3 bar discharge

Problem: Bearing temperature rising 70°C → 85°C over 6 months. Vibration stable but heat trend alarming. Oil analysis showed 2,000 ppm water—triple acceptable limit.

Root cause: Refrigerated dryer downstream failing—not removing moisture from compressed air. Compressed air moisture → water accumulation in bearing sump → bearing corrosion.

Solution: Replaced dryer, flushed bearing sump with fresh oil, verified inlet air dew point <-30°C (dry).

Result: Bearing temperature dropped 85°C → 65°C within weeks. Oil analysis 6 months later: <200 ppm water (acceptable). No bearing damage occurred—early detection (vibration trending + thermal monitoring + oil analysis) prevented catastrophic failure.

Lesson: Auxiliary systems (dryers, filters) critical—neglect causes bearing damage invisible in vibration data until failure imminent.

Case Study 3: Shell UK North Sea Platform (Offshore)

Application: Centrifugal compressor driving high-pressure methanol synthesis, 25,000 RPM, 50 m³/h flow, 250 bar discharge

Challenge: Rotor imbalance causing 1x RPM vibration 3.5 mm/s RMS (yellow severity per ISO 10816). Bearing tilting-pad temperature 78°C (approaching 80°C limit).

Root cause: Impeller erosion from entrained sand particles (0.1-0.5 mm diameter) in inlet gas. Erosion distributed unevenly = imbalance increased from 0.0005 in/s to 0.003 in/s over 3 months.

Solution: Installed inlet separator (removes particles >5 μm). Rebalanced compressor to 0.0005 in/s (ISO Grade 1.0). Result: Vibration 3.5 → 1.2 mm/s RMS. Bearing temperature 78°C → 62°C.

Lesson: Inlet condition critical—sand/salt/water particles degrade impeller surface, causing progressive imbalance and bearing heating.

Step-by-Step Centrifugal Compressor Commissioning

Pre-Startup Checklist (50+ items) (1 week before):

- Foundation alignment: <0.002″ TIR per ISO 1940

- Rotor run-in: Hand-turn coupling freely (no binding)

- Bearing lube oil: Correct grade, filled to sight-glass 50-75%, temperature 40-50°C

- Seal flush plan: Flow verified, pressure correct

- Instrumentation: Pressure gauges, temperature sensors, vibration transducers calibrated

- Anti-surge valve: Response time verified (<500 ms)

- Valve settings: Relief pressure, inlet guide vane position confirmed

- Piping: Hydrostatic test completed, no leaks

Slow-Speed Rotation (100 RPM, 5 minutes):

- Motor direction verified (correct rotation)

- No bearing binding or mechanical rubbing

- All rotating parts free

- Vibration baseline established (typically <0.5 mm/s at low speed)

Ramp-Up to Operating Speed (2-3 hours):

- Speed increase rate: 500 RPM/minute maximum (prevents transient pressure spikes)

- Monitor pressure buildup (should match performance curve)

- Monitor bearing temperature (should rise gradually to 55-65°C)

- Monitor vibration (should remain <2.3 mm/s RMS—ISO 10816 “good”)

- No surge oscillations should occur during ramp-up

Performance Verification (4+ hours continuous operation):

- Discharge pressure: ±3% of design

- Flow rate: ±5% of design (measure with orifice plate or turbine meter)

- Bearing temperature: <70°C normal, <75°C maximum

- Vibration: <2.3 mm/s RMS (ISO 10816 “good”)

- Seal integrity: <5 drops/minute acceptable

Acceptance Test (full load, 24 hours continuous):

- Vibration trending: confirm stable (not increasing over 24 hours)

- Oil analysis: particle count, water content, acid number baseline

- Pressure/temperature/vibration: document every 2 hours (12 data points)

- As-built drawing: alignment, torque values, baseline vibration, acceptance data

Advanced Centrifugal Compressor Maintenance

Daily (10 minutes):

- Visual inspection: leaks, corrosion, coupling alignment

- Listen: normal sound (no grinding, whistling, knocking)

- Bearing temperature: IR thermometer, record if >70°C

Weekly (30 minutes):

- Full vibration measurement: 3-point protocol (vertical, horizontal 1, horizontal 2)

- Oil level: sight glass 50-75%, top-up if needed

- Anti-surge valve function: verify opens smoothly under load

- Seal integrity: <5 drops/minute is acceptable

Monthly (1 hour):

- Oil analysis: particle count (ISO 4406 code), water content, viscosity, TAN

- Pressure/flow/temperature trending: plot on graph, check for degradation

- Coupling inspection: backlash <0.010″, no visible wear

- Bearing play measurement: should remain <0.001″ radial clearance

Quarterly (4 hours):

- Impeller clearance measurement: end-play per design spec

- Anti-surge valve overhaul: clean orifices, verify spring force

- IGV linkage inspection: smooth movement, no stiction

- Rotor balance verification: compare current vibration to baseline

Annual (1 day):

- Bearing removal and inspection: white metal condition, corrosion, clearance

- Seal replacement: if operating >8,000 hours

- Full performance test: pressure/flow vs. design curve

- Alignment reverification: laser check TIR tolerance

Common Centrifugal Compressor & Fan Failures

Surge Damage (40% of catastrophic failures): Pressure oscillations destroy bearings, seals, couplings. Prevention: anti-surge valve, inlet guide vanes, VFD trim.

Bearing Failure (30%): Misalignment, water contamination, lube oil degradation. Prevention: laser alignment, oil analysis monthly, water separator maintenance.

Seal Leakage (15%): Cavitation-induced movement, thermal stress, contamination. Prevention: flush plan per API, thermal monitoring.

Impeller Erosion (10%): Sand particles from inlet air. Prevention: inlet separator, air filter maintenance.

Rotor Imbalance (5%): Erosion wear, bearing play growth, manufacturing defect. Prevention: quarterly vibration checks, field balancing tolerance <0.001 in/s.

Conclusion: Master Centrifugal Turbomachinery Engineering

Bottom line:

✅ Centrifugal compressors/fans operate 50+ million units globally—understanding them = career advantage

✅ Design fundamentals: aerodynamic pressure recovery, rotor dynamics, bearing lubrication determine reliability

✅ Surge prevention: multi-layer defense (ASV + VFD + IGV) prevents $500K+ catastrophic failures

✅ Maintenance discipline: monthly vibration + oil analysis predicts failures 30+ days early

✅ Global standards: API 617, ISO 10816 define safe operation