Introduction

Compressors are indispensable machines in modern industrial applications, from manufacturing plants and power generation facilities to HVAC systems and oil refineries. A compressor is a mechanical device that reduces the volume of a gas, thereby raising its pressure and temperature for subsequent use in various processes. Understanding the different types of compressors and their specific industrial applications is crucial for engineers, plant managers, and procurement professionals to select the right equipment for their needs.

The global compressor market serves countless industries, each with unique requirements for pressure output, flow rate, efficiency, and air purity. Selecting an inappropriate compressor type can lead to inefficient operations, excessive energy consumption, and costly downtime. This comprehensive guide explores the major compressor types—reciprocating, rotary screw, centrifugal, and axial—their working principles, advantages, disadvantages, and real-world industrial applications.

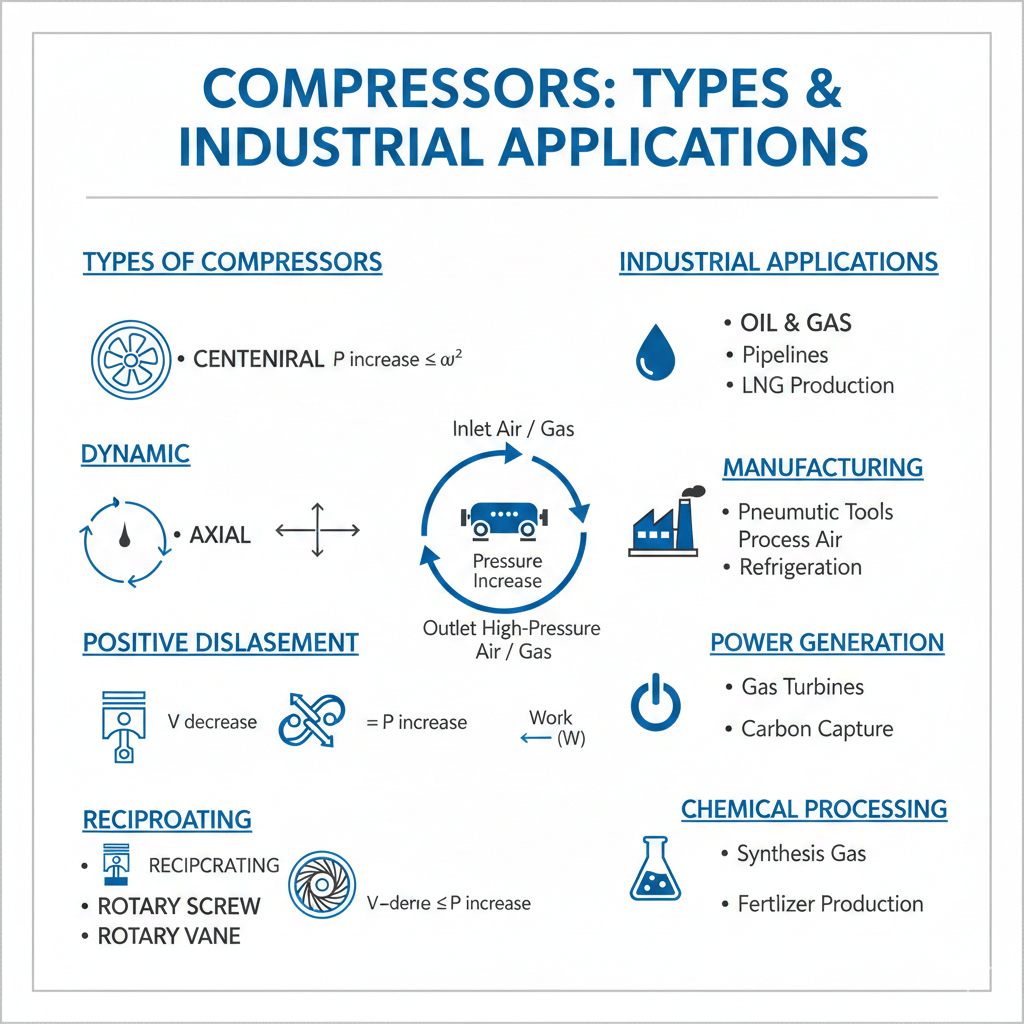

Understanding Compressor Basics: Positive Displacement vs. Dynamic Compression

Before diving into specific compressor types, it’s essential to understand the two fundamental compression methodologies that underpin all industrial compressors: positive displacement compression and dynamic compression.

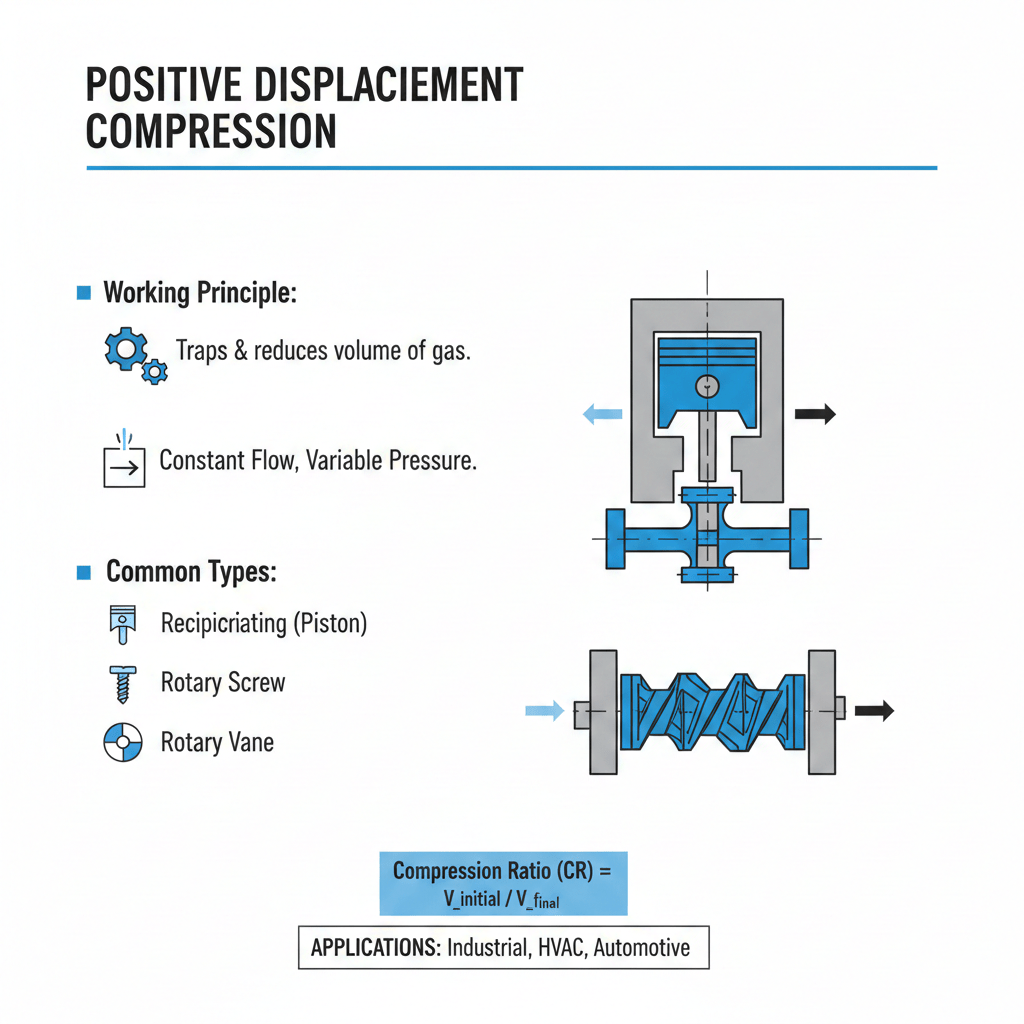

Positive Displacement Compression

Positive displacement compressors work by trapping a fixed volume of gas in an enclosed space, then reducing that volume to increase the pressure. This direct compression method ensures a more constant output flow rate regardless of discharge pressure, making these compressors ideal for applications requiring high pressure at varying load conditions.

The key characteristic of positive displacement machines is that their power requirement is primarily driven by flow rate (CFM—cubic feet per minute) rather than discharge pressure (PSI—pounds per square inch). This means a positive displacement compressor will deliver consistent flow even as system pressure fluctuates, though the power required to achieve this remains relatively constant.

Dynamic Compression

Dynamic compressors, conversely, achieve compression by accelerating gas molecules and converting their kinetic energy into pressure through a diffuser section. As gas velocity increases, the pressure rises correspondingly. This compression method is particularly efficient for handling large volumes of gas at moderate to high pressures and is the principle behind centrifugal and axial compressors.

In dynamic compressors, the power requirement is primarily dependent on the mass flow rate (weight of gas) being compressed. Increasing discharge pressure reduces the volume of usable air at the same input horsepower, making these compressors well-suited for high-volume, continuous-duty applications.

Major Compressor Types and Their Characteristics

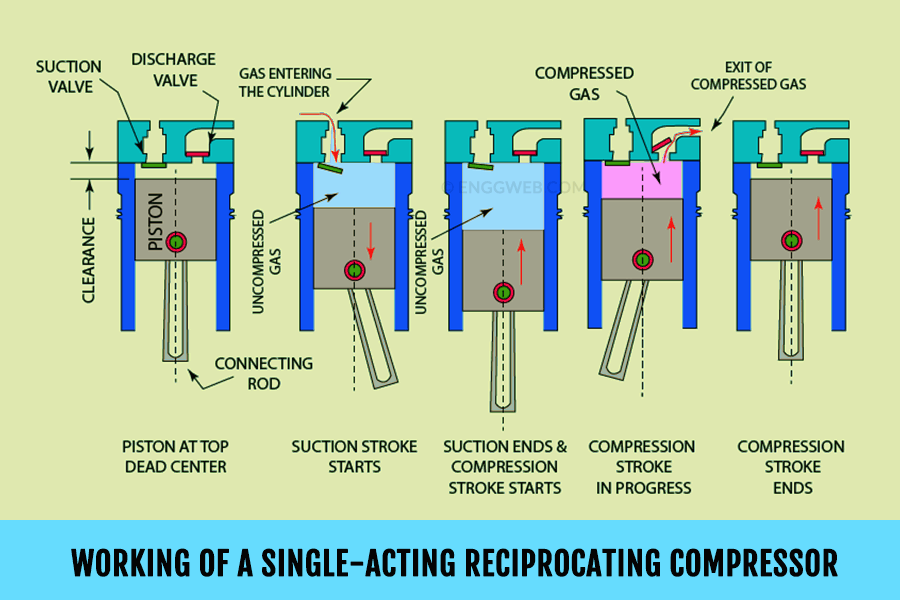

1. Reciprocating Compressors (Piston-Type Compressors)

Working Principle

Reciprocating compressors represent the most common positive displacement design and operate on a simple but effective principle. A piston moves back and forth within a cylinder, creating alternating suction and discharge strokes. During the suction stroke, the piston moves backward, creating a low-pressure area that opens the suction valve, allowing ambient or pre-compressed gas to enter the cylinder. The intake valve then closes, and during the discharge stroke, the piston compresses the trapped gas, raising its pressure until it exceeds the discharge pressure, opening the discharge valve and forcing the compressed gas into the delivery system.

Advantages of Reciprocating Compressors

Reciprocating compressors offer several compelling advantages that explain their widespread adoption:

- High-Pressure Capability: Reciprocating compressors can generate extremely high discharge pressures—up to 30,000 PSI or more—making them ideal for applications requiring ultra-high pressure. They can operate effectively at pressure ratios ranging from 1.1 in low-pressure applications to over 10 in high-pressure systems.

- High Efficiency for Intermittent Duty: These compressors require relatively less energy to produce high-pressure gases, making them exceptionally efficient for applications with intermittent compressed air requirements and variable load conditions.

- Flexibility and Versatility: Reciprocating compressors can handle a broad range of output capacities, from as small as 1 horsepower (HP) to more than 600 HP, allowing them to serve both small workshops and large industrial facilities.

- Durability and Reliability: With proper maintenance, reciprocating compressors exhibit excellent longevity, often operating reliably for many years with minimal component replacement.

- Compact Design: Compared to some alternatives, reciprocating compressors occupy relatively little floor space, making them suitable for installations with spatial constraints.

Disadvantages of Reciprocating Compressors

Despite their advantages, reciprocating compressors have notable limitations:

- Vibration and Noise Generation: The reciprocating motion inherently creates vibration and produces high noise levels during operation, often exceeding 80 decibels. This requires substantial foundations, vibration isolation mounts, and acoustic enclosures in noise-sensitive environments.

- Limited Continuous-Duty Capacity: Reciprocating compressors are not optimally designed for continuous, long-duration operation at maximum capacity. Intermittent use with periodic rest periods yields better performance and longevity.

- High Discharge Temperature: The compression process generates significant heat; discharge air temperatures typically reach 250–300°F, requiring downstream cooling and heat management systems.

- Inability to Self-Regulate: Unlike rotary compressors, reciprocating units cannot automatically adjust output to match system demand. They will continue displacing gas until manually controlled or until internal pressure switches activate.

- High Maintenance Requirements: Piston rings, valves, gaskets, and rod bearings experience significant wear and require periodic inspection and replacement. Oil carry-over is typical, requiring downstream air treatment if contamination-free air is needed.

Industrial Applications

Reciprocating compressors excel in applications such as:

- Pneumatic tool operation in machine shops and automotive service centers

- High-pressure gas cylinders and bottle filling operations

- Refrigeration systems in commercial freezers and cold storage facilities

- Natural gas processing and pipeline booster applications

- Mobile compressors for construction sites and portable pneumatic systems

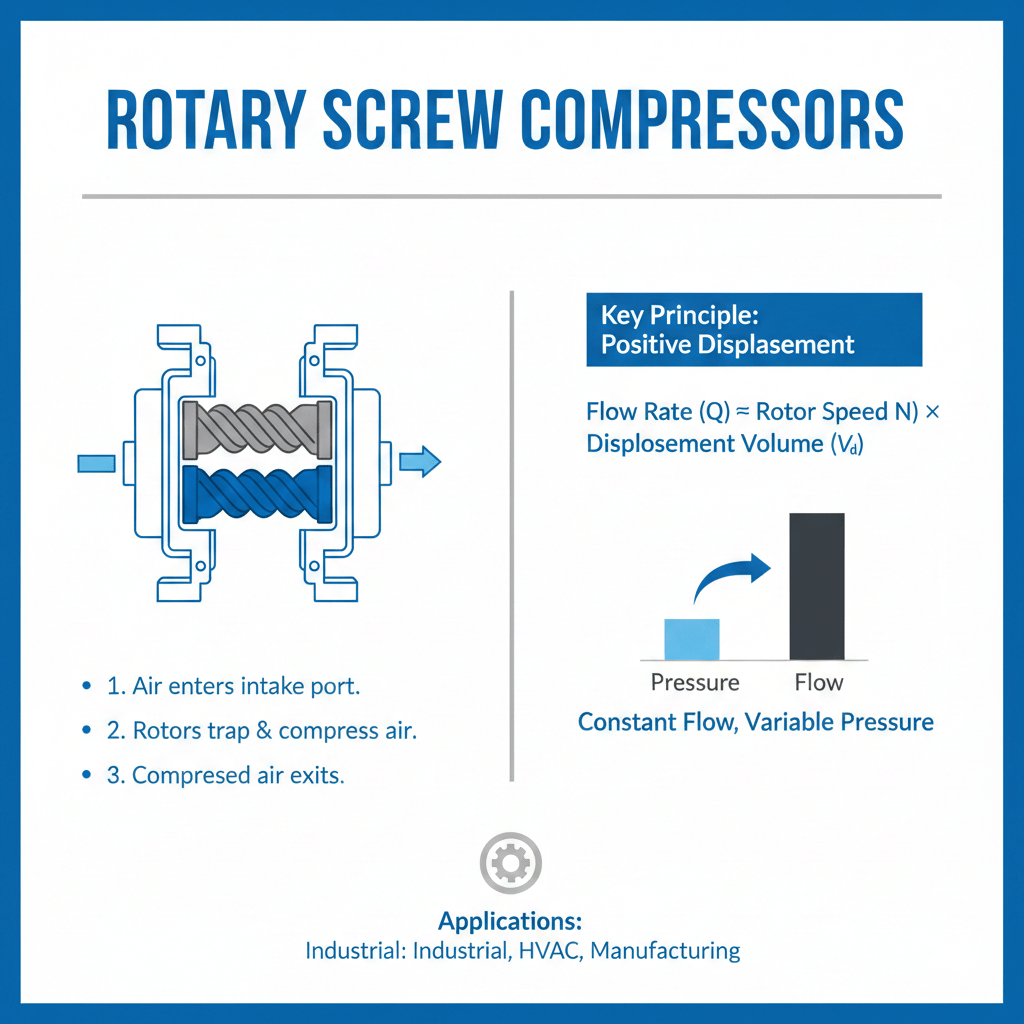

2. Rotary Screw Compressors

Working Principle and Design

Rotary screw compressors represent a positive displacement design that has largely replaced reciprocating units in many industrial settings. The compressor features two helically cut rotors—a male profile rotor and a female profile rotor—that mesh together and rotate in opposite directions. As the rotors turn, the volume between them and the compressor housing decreases, trapping and progressively compressing the gas.

The compression process occurs in three stages: intake (gas enters through the inlet port), compression (as the rotor profiles reduce the chamber volume), and discharge (compressed gas exits through the discharge port). Oil is typically injected into the compression chamber in conventional designs to provide lubrication, cooling, and additional sealing between rotor clearances.

Oil-Flooded vs. Oil-Free Designs

Rotary screw compressors are available in two primary configurations:

Oil-Flooded Compressors: In this configuration, oil is injected throughout the compression chamber, providing multiple benefits:

- Superior Efficiency: Oil lubrication minimizes friction between moving parts, reducing energy consumption compared to oil-free designs. A typical single-stage oil-flooded screw compressor operates at approximately 22 bhp/100 acfm (brake horsepower per 100 actual cubic feet per minute).

- Lower Noise and Vibration: The oil acts as a damping medium, significantly reducing operational noise—often 10–15 decibels lower than oil-free equivalents.

- Extended Component Lifespan: Oil lubrication reduces wear and tear on internal components, extending the service life of bearings, rotors, and seals.

- Lower Initial Cost: Oil-flooded designs are less expensive to manufacture than oil-free alternatives.

The primary disadvantage is that compressed air contains residual oil—typically 3 ppm (parts per million)—requiring downstream oil removal equipment for sensitive applications.

Oil-Free Compressors: Oil-free designs utilize special rotor coatings or water injection to minimize friction:

- 100% Pure Air: Compressed air is completely free of oil contamination, making these compressors ideal for pharmaceutical, food and beverage, semiconductor, and medical applications where air purity is non-negotiable.

- Reduced Maintenance: Without oil circulation, there are no oil changes, oil filter replacements, or oil disposal requirements, substantially reducing maintenance costs and environmental impact.

- Regulatory Compliance: Oil-free compressors meet stringent air purity standards mandated in regulated industries, such as ISO 8573 Class 1 compressed air purity.

Oil-free compressors generate more noise than oil-flooded units and command a higher initial purchase price, though their lower operational maintenance costs can offset this premium over the compressor’s lifetime.

Advantages of Rotary Screw Compressors

- Continuous Operation: Unlike reciprocating units, screw compressors are designed for continuous duty and can operate 24/7 without performance degradation.

- Clean, Consistent Output: Rotary screw compressors deliver smooth, pulsation-free compressed air with minimal pressure fluctuation.

- Low Noise Levels: Oil-flooded designs operate at 70–80 decibels, comparable to normal conversation, making them suitable for indoor locations and noise-restricted environments.

- Wide Capacity Range: Available from small portable units to large industrial installations delivering thousands of CFM.

- Self-Regulating Models Available: Many modern screw compressors feature variable displacement or inlet valve modulation, automatically adjusting output to match system demand and reducing energy waste during partial-load operation.

Disadvantages of Rotary Screw Compressors

- Lower Pressure Ratios: Single-stage rotary screw compressors typically achieve pressure ratios of 4–8, limiting applications requiring extremely high discharge pressures (though two-stage designs can achieve higher ratios).

- Complex Internal Geometry: The precise rotor profiles and clearances require sophisticated manufacturing, making repairs expensive and necessitating OEM replacement parts.

- Pressure Sensitivity to Load Changes: Screw compressors are more sensitive to load and pressure fluctuations than reciprocating designs, requiring careful system design and appropriate air receiver sizing.

Industrial Applications

Rotary screw compressors are the dominant choice for:

- General manufacturing plant compressed air systems (production tools, assembly lines, painting systems)

- Automotive assembly plants and service facilities

- Food and beverage processing (oil-free designs)

- Pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing (oil-free designs)

- Semiconductor fabrication facilities (oil-free, ultra-clean air)

- Printing and textile operations

- Construction equipment power supplies

- Mining ventilation and pneumatic tool operation

3. Centrifugal Compressors (Turbo Compressors)

Working Principle and Operation

Centrifugal compressors represent the dynamic compression category and operate on fundamentally different principles than positive displacement units. These machines utilize a rotating impeller (similar to a turbine wheel) to accelerate gas radially outward, converting the kinetic energy of the moving gas into pressure as it enters a diffuser section.

The compression process involves three stages: acceleration (the impeller imparts kinetic energy to gas molecules, causing radial acceleration), turning speed into pressure (in the diffuser section, the expanding passage slows the high-velocity gas, converting kinetic energy into static pressure), and discharge (the gas enters a volute or scroll chamber where further pressure increase occurs through additional diffusion before discharge).

For applications requiring very high pressure ratios, multiple compressor stages can be arranged in series, with intercoolers between stages to reduce discharge temperature and improve overall efficiency.

Advantages of Centrifugal Compressors

- High-Volume Flow Rates: Centrifugal compressors excel at handling large volumes of gas, making them essential in applications requiring thousands of CFM.

- Oil-Free Operation: By design, centrifugal compressors discharge completely oil-free, high-purity compressed air, eliminating the need for downstream oil removal systems.

- Smooth, Vibration-Free Operation: The continuous rotational motion produces pulsation-free, vibration-free compressed air, enabling smooth operation of sensitive downstream equipment.

- Compact Design Per Unit Flow: For very high flow rate requirements, centrifugal compressors offer the smallest footprint and lowest space requirement compared to alternative technologies.

- Excellent Efficiency at Rated Conditions: Modern centrifugal compressors achieve isentropic efficiencies of 80–82%, comparable to or exceeding rotary screw designs when optimally operated.

- Speed Control and Part-Load Efficiency: Variable-speed drive options allow centrifugal compressors to adjust operating speed based on load, maintaining high efficiency across a range of operating conditions.

Disadvantages of Centrifugal Compressors

- Lower Single-Stage Pressure Ratios: A single centrifugal stage typically achieves pressure ratios of 3–5, substantially lower than reciprocating (6+) or rotary screw (4–8) designs. Multi-stage configurations are required for higher pressures.

- Minimum Flow Requirements: Centrifugal compressors must operate above a minimum flow threshold to avoid surge (an instability condition where flow reverses), limiting their applicability to low-demand applications without air receiver storage.

- Sensitivity to Operating Conditions: Performance is significantly affected by inlet gas properties (temperature, humidity, composition), requiring careful process control and instrumentation.

- Higher Initial Capital Cost: Centrifugal compressors command premium prices compared to reciprocating or screw designs, particularly for custom applications.

- Specialized Maintenance Requirements: Repairs typically require specialized expertise and OEM involvement; field repairs are limited.

Industrial Applications

Centrifugal compressors dominate applications such as:

- Petrochemical processing and natural gas liquefaction

- Large HVAC systems for commercial buildings and industrial facilities

- Power generation plants requiring massive air volumes

- Compressed air systems in semiconductor manufacturing facilities

- Electronics cooling applications requiring oil-free air

- Air separation units (nitrogen, oxygen production)

- Large refrigeration systems and industrial cooling

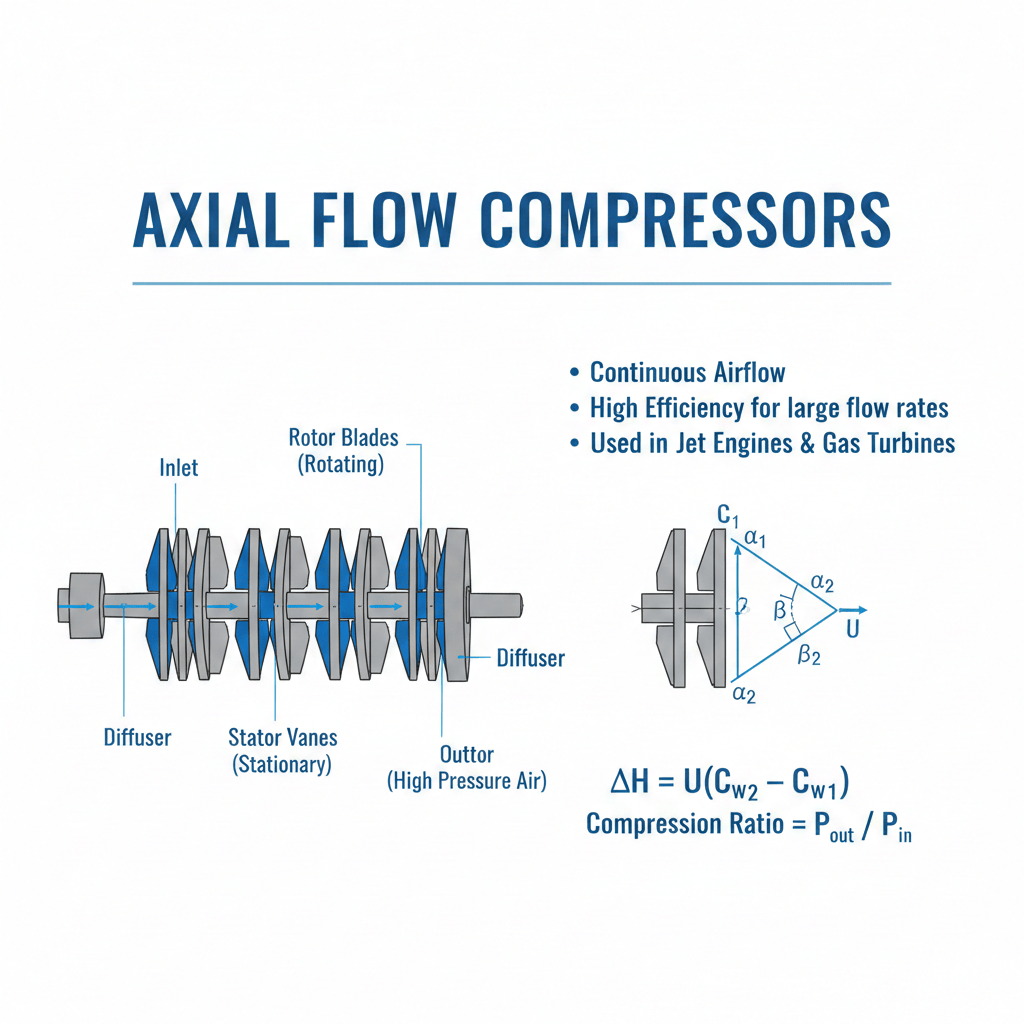

4. Axial Flow Compressors

Working Principle

Axial flow compressors feature multiple rows of rotating blades (rotors) and stationary blades (stators) arranged along the compressor’s longitudinal axis. Gas flows essentially parallel to the compressor centerline, being compressed progressively as it passes through successive blade stages. Each rotor-stator pair forms a compression stage, and modern turbines may incorporate 10–15 stages to achieve required pressure ratios.

The working principle mirrors centrifugal compressors in converting kinetic energy to pressure but differs fundamentally in the direction of gas flow and blade arrangement, requiring numerous stages to build significant pressure.

Advantages of Axial Flow Compressors

- Exceptional Peak Efficiency: Axial compressors achieve isentropic efficiencies of 86–90% under optimized conditions, the highest among all compressor types.

- Extremely High Mass Flow Rates: These compressors handle mass flow rates exceeding 100 kg/s, far surpassing centrifugal capabilities for a given size.

- Minimal Frontal Area: The axial flow arrangement provides the smallest cross-sectional area for a given flow rate, enabling compact, lightweight designs.

- Straight-Through Flow Path: The parallel-to-axis flow direction minimizes pressure losses, enabling high ram efficiency in aerospace applications.

Disadvantages of Axial Flow Compressors

- Moderate Single-Stage Pressure Ratios: Individual stages achieve pressure ratios around 1.25, requiring many stages for substantial pressure increases.

- Manufacturing Complexity and Cost: Precise blade aerodynamics, high-tolerance manufacturing requirements, and multi-stage construction make these compressors extremely expensive (often 2–3 times more costly than centrifugal units).

- Aerodynamic Sensitivity: These compressors are prone to surge and stall if operating conditions deviate from design point, requiring sophisticated control systems.

- Maintenance Challenges: Complex blade arrangements and aerodynamic considerations make field repairs difficult, requiring specialized expertise.

- High Starting Power Requirements: Initiating rotation requires substantial power input, necessitating soft-start systems or variable-frequency drives.

Industrial Applications

Axial compressors are reserved for specialized high-performance applications:

- Jet engine air intake compression (most critical aerospace application)

- Large gas turbine power generation

- Industrial gas turbines

- Specialized industrial applications requiring extreme efficiency and high mass flow rates

Compressor Selection Criteria and Calculation Methods

Selecting the appropriate compressor type requires careful analysis of application requirements. The primary decision parameters are:

1. Pressure Requirements (PSI)

- Low Pressure (0–50 PSI): Typically served by rotary screw or centrifugal compressors

- Medium Pressure (50–250 PSI): Primary domain of reciprocating and rotary screw compressors

- High Pressure (250–3,000 PSI): Reciprocating compressors with single or multiple stages

- Ultra-High Pressure (>3,000 PSI): Specialized reciprocating designs only

2. Flow Rate Requirements (CFM)

Flow rate determines compressor size and horsepower. The basic relationship is:

CFM = (Horsepower × CFM per HP at specified PSI) / Correction Factor

For example, at 100 PSI, a 10 HP rotary screw typically delivers approximately 34 CFM, while the same horsepower reciprocating unit delivers about 20 CFM.

3. Duty Cycle Considerations

- Intermittent (0–25% utilization): Reciprocating compressors offer efficiency advantages

- Part-Load (25–75% utilization): Rotary screw with modulation or variable displacement

- Continuous (75–100% utilization): Rotary screw or centrifugal compressors

4. Air Quality Requirements

- Standard Industrial Air (3–5 ppm oil): Oil-flooded rotary screw

- Clean Air (<1 ppm oil): Oil-flooded screw + downstream dryer/filter

- Oil-Free Air (0 ppm oil): Oil-free rotary screw or centrifugal compressors

- Ultra-Pure Air (ISO 8573 Class 1 or better): Oil-free screw or centrifugal + specialized filtration

Common Compressor Failure Modes and Preventive Maintenance

Understanding failure mechanisms is critical for maintaining system reliability and minimizing unplanned downtime.

Primary Failure Modes

Overheating is the most common compressor failure, accounting for numerous premature component failures. Causes include fouled air intake filters, blocked cooler passages, poor ventilation around the compressor enclosure, high ambient air temperature, and insufficient or degraded lubrication oil.

Oil-Related Failures include insufficient lubrication (causing bearing scoring and seizure), oil dilution (reducing lubricant effectiveness and promoting sludge formation), and oil leaks (contaminating the environment while reducing film protection).

Valve and Seal Degradation occurs when deposits accumulate on valve surfaces, gaskets lose elasticity due to thermal cycling and contamination, and bearing surfaces experience accelerated wear.

Vibration-Related Issues result from unbalanced rotors, loose foundation bolts, worn bearings, and inadequate lubrication, causing premature component failure.

Pressure Control Problems include stuck or malfunctioning pressure switches, air leaks in discharge or intake passages, and regulator failures.

Preventive Maintenance Strategy

A robust maintenance program should include:

- Weekly Inspections: Visual checks for oil leaks, unusual noises, excessive vibration, and cooling fan operation

- Monthly Tasks: Air filter inspection and cleaning, oil level verification, pressure gauge monitoring

- Quarterly Maintenance: Oil and filter changes (for oil-lubricated units), cooler cleaning, valve and gasket inspection

- Annual Deep Inspections: Bearing play assessment, seal condition evaluation, complete system pressure testing, electrical system verification

Conclusion

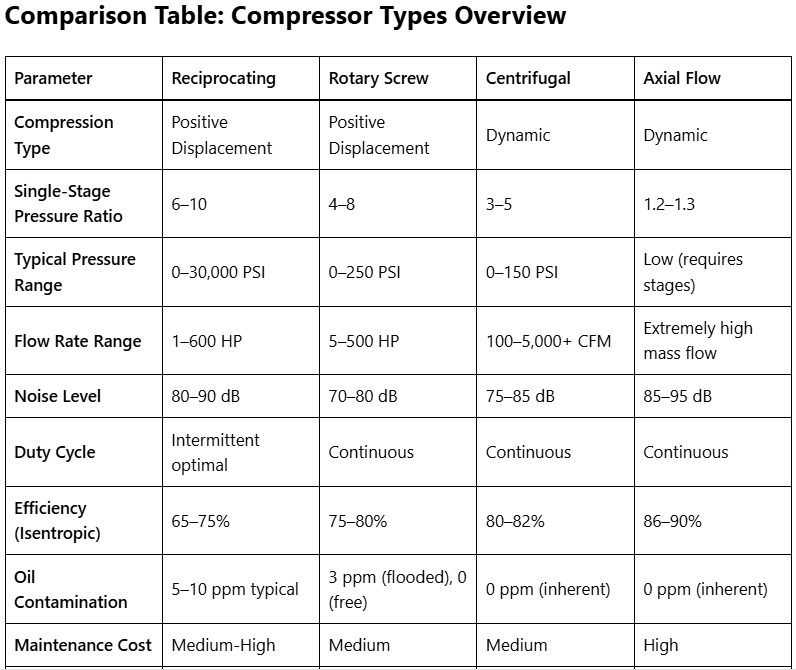

The selection of an appropriate compressor type is fundamental to achieving operational efficiency, reliability, and cost-effectiveness in industrial applications. Reciprocating compressors remain indispensable for high-pressure applications and intermittent duty cycles. Rotary screw compressors have become the industry standard for general-purpose compressed air systems due to their reliability, efficiency, and continuous-duty capability. Centrifugal compressors excel in high-volume applications requiring clean, vibration-free air. Axial flow compressors serve specialized aerospace and power generation applications where extreme efficiency and mass flow rates justify their considerable cost.

By understanding the working principles, advantages, limitations, and industrial applications of each compressor type, engineers and plant managers can make informed decisions that optimize system performance, minimize energy consumption, and ensure long-term operational reliability. Coupled with a comprehensive preventive maintenance program, proper compressor selection ensures maximum return on investment and supports uninterrupted production operations.

Key Takeaways

- Positive displacement compressors (reciprocating and rotary screw) provide more constant flow regardless of pressure, while dynamic compressors (centrifugal and axial) excel at high-volume applications.

- Reciprocating compressors achieve the highest single-stage pressure ratios (6–10) and are best for intermittent, high-pressure applications but generate significant noise and vibration.

- Rotary screw compressors dominate the industrial market, offering excellent efficiency for continuous duty with two variants: oil-flooded (cost-effective, lower noise) and oil-free (ultra-clean air for sensitive industries).

- Centrifugal compressors provide inherently oil-free, smooth-running operation ideal for pharmaceutical, food, and semiconductor applications but require multi-stage designs for high pressure.

- Proper compressor selection depends on analyzing required pressure (PSI), flow rate (CFM), duty cycle, and air quality standards for your specific application.

- Preventive maintenance—including regular filter changes, oil analysis, cooler cleaning, and bearing inspection—prevents 80% of compressor failures and extends equipment lifespan.